Benjamin Winans

Communion

Communion: to share one's intimate thoughts, especially in spiritual matters. When we examine the systems of belief that define us, what is exposed? In this exhibition, I propose art practice as communion, offering my southern Evangelical Christian upbringing - my doubts, my loss of faith - to you. My questioning is manifested in the altered ruins and artifacts of American Christianity, presented to test their relationships to history and to reveal greater societal undercurrents, asking us to imagine reckoning and reconciliation. The following photos are of my MFA thesis exhibition, comprised of photographs, sound work, video, sculpture, and installation.

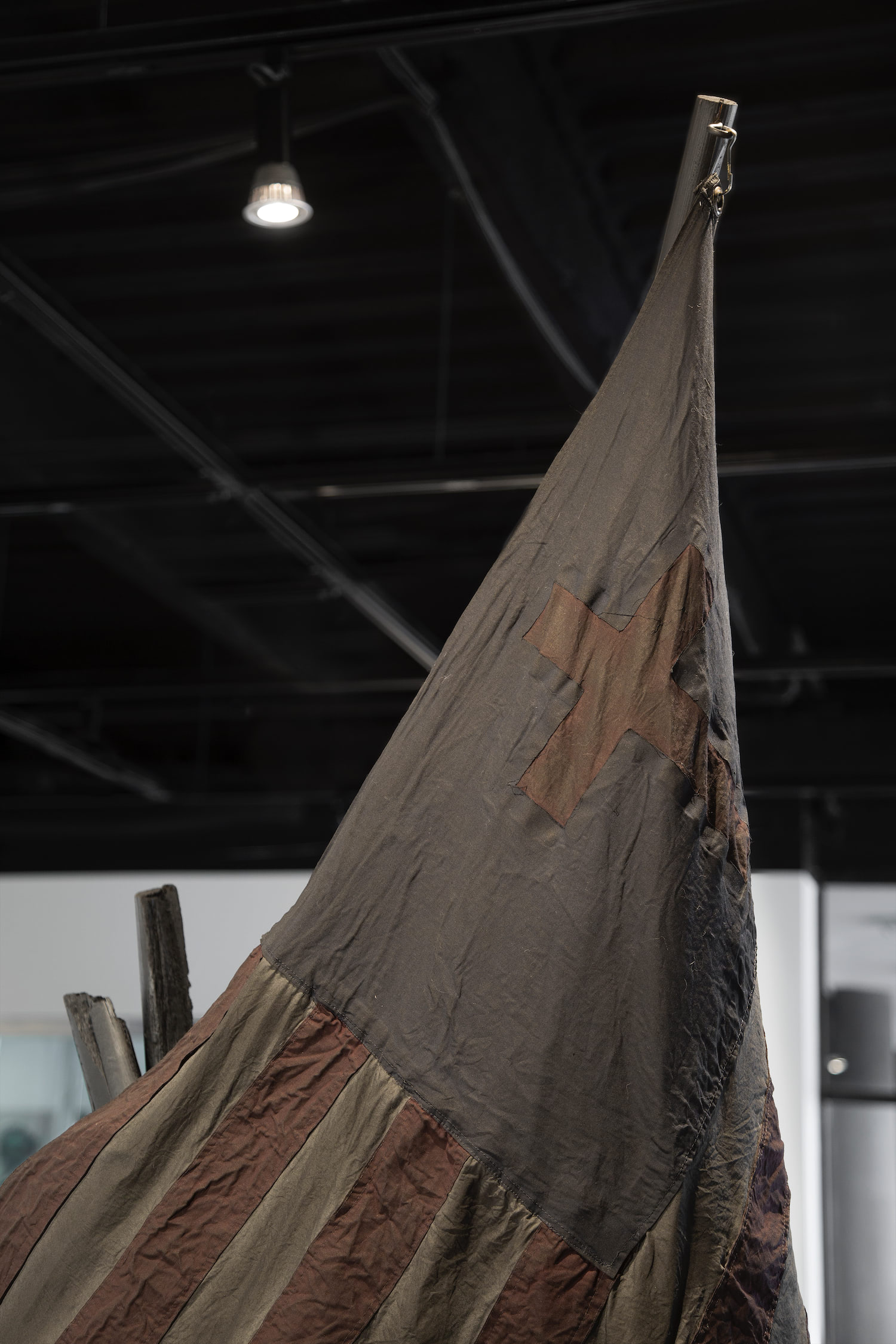

When we examine the systems of belief that define us, what is exposed? In order to dig into this question, I explore what communications scholar Carolyn Kitch has described as public memory – “these identities, national and regional as well as social and individual, are located on the edge of our lives, hovering, ready to be invoked or revised, acted upon or merely contemplated, inspiring us or boring us.” The first piece of mine encountered as you enter Stamps Gallery is this sculpture titled “Reckoning” (98″ x 63″‘ x 30″). It is constructed from church pews, broken apart with an ax, built up, set on fire, saved, and blackened with a torch. It is created to reference two artifacts that live powerfully in the public memory of Americans: the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima, and Emanuel Leutze’s famous painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware”. Each of these works inspires patriotism, nationalism, and exceptionalism. In the case of the photo from Iwo Jima, the form has been sculpted and cast in bronze, and was used to inspire the National Marine Museum in Quantico, VA, each in monumental form. “Reckoning” adopts the language of monumentality; a piece fixed in time, but something is also terribly wrong. It looks as though it is deconstructing itself, bursting from the plinth that contains it, holding onto its pieces, and struggling to hold its flag high.

The flag itself is not the American flag as is represented in the famous references. It is instead a mixing of the American flag and the lesser-known Christian flag (invented in the 1890s as a flag to represent all Christendom). Put together, they represent the end goal of the Christian Nationalist movement: a theocratic society built on a corrupted view that God has chosen the United States, and that its citizens must follow a certain view of the scriptures in order to maintain his blessing upon the nation.

Thus presented, I begin my exhibition by asking the viewer to question relationships between Christianity and patriotism, nationalism, and iconography.

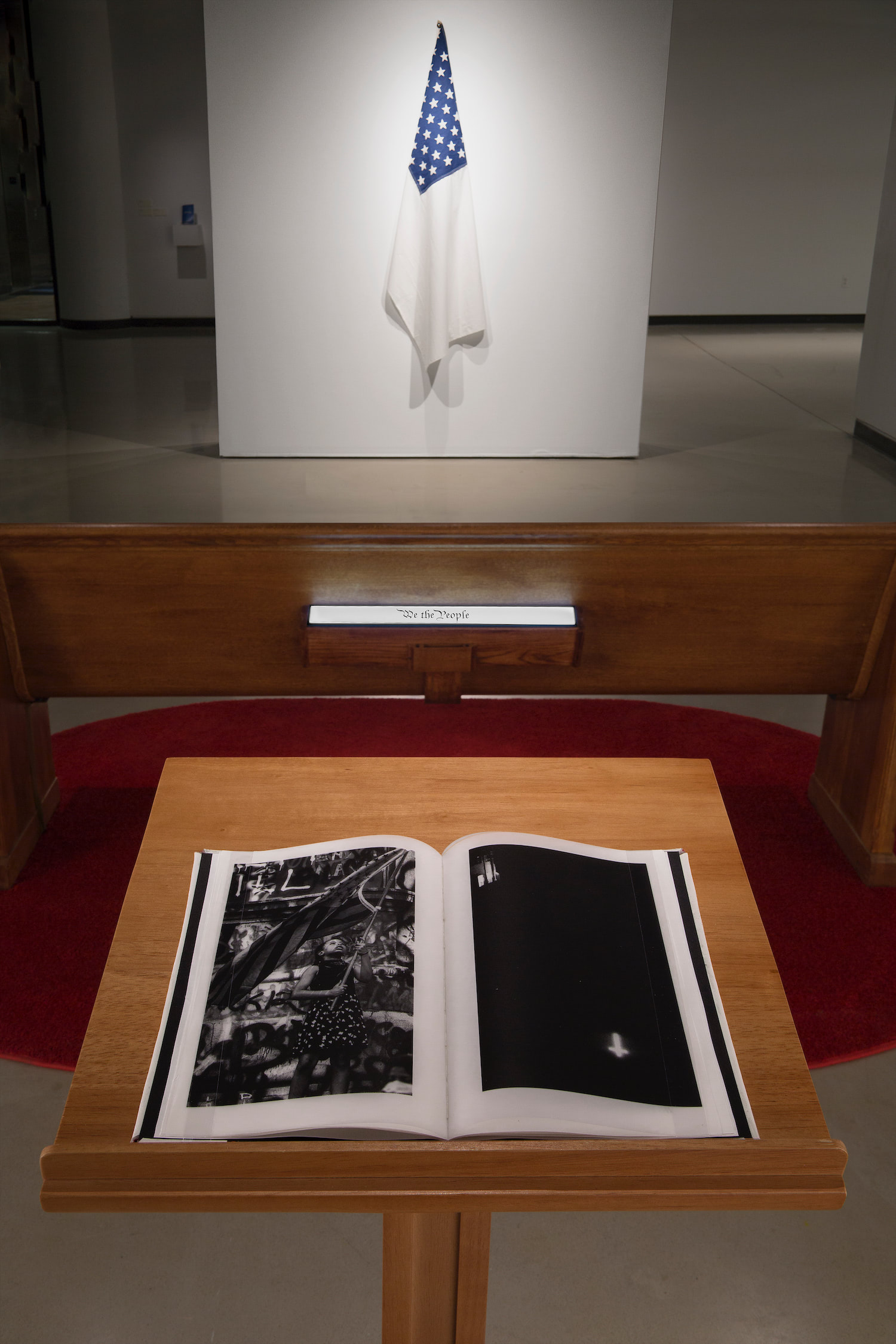

In the center of the chapel-like gallery sits what looks like a normal pew on a red carpet. The pew faces a flag, limply hanging on a white wall. It is the recognizable blue with white stars of the American flag, but the red stripes, representing the blood of patriotism and courage shed for the freedom of Americans, have been removed, leaving the field bleached cotton. In form, there is the realization that hanging as it is, the flag looks like the floating hood of a Klansman. Once the Klan hood is recognized, one may remember the rubble of pews in Reckoning, and how, if history is considered, they evoke the public memory of church burnings and bombings: specific targets of white domestic terrorists to disrupt the church, which is the historic heart of the community. With the understanding that certain violence underscores my work, an investigation of the title card of the pew itself reveals that it has been refinished with blood — information only accessible by the astute observer. Forming an inverted conversation with the symbolic absence in the flag, the very real corruption of the pew itself lies under a surface that looks entirely ordinary.

Behind the pew is a pedestal supporting a handmade book (7.5″ x 9.5″), bound in dual-tone black and white leather with a strip of red fabric running between the two. Mounted in the hymn rack of the pew is a small screen (2″ x 24″) that displays intermittent text taken from the bible (written in Gutenberg’s blackletter he used to print his famous bible) and the US Constitution (written in a script inspired by the handwriting of Timothy Matlack, who engrossed of the Declaration of Independence).

This video compares the language of two famous “sacred” documents: the Bible, believed to be “God-breathed” by Christians, and the US Constitution, a document which 68.4% of white Protestant Christians view as “divinely-inspired” according to sociologists Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry. The chosen language exhibits phrases taken to highlight how we in society should be treating those less fortunate: that sees the rich giving everything of themselves for the sake of the poor; that sees the powerful humbled and on bended knees, ready to empower the lives of others. This view forms a contrast to that heard from the pulpits of televangelists and celebrity preachers across the country.

The book on the pedestal is titled “Between These Worlds”. It forms a dual artist statement, printed in a tête-bêche style (one statement in one direction, the other backward and meeting in the middle). On a shelf, one doesn’t know which statement one may start with. This is important as I have made 30 of these books, to be donated to libraries in both academic institutions and churches.

The statements make up a critique of both the church and the academic world for not doing their part to bridge the gap evident between them – for the church, the drive to aid humanity by imaging a better world, for the academic, the ignorance with which the “Ivory Tower” distances itself from the real issues of existence.

Deconstruction, 30″ x 40″. This photo hangs on the right wall as the viewer stands behind the pew looking at the flag. It is a self-portrait, not meant to be an art piece, but more a documentation of process and a queue to contemplation.

Deconstruction II, 30″ x 40″. This second documentary self-portrait hangs on the wall to the left as you look towards the flag. It is another work not meant to be an art piece, but documentation of the process. It was made after our class lost access to our studio last spring, and during a tumultuous summer that saw protests against police violence and a call to address racial injustice spread across the country. It was over the summer that I stepped back from making and began processing the nature of my own Christian deconstruction and its relationship to the political climate of America.

Phantom Limb. Found church pew, fire, bronze, and wood, 51.5”x 89.25”x 29”.

The photo of the sculpture, placed in a church sanctuary, is a key piece in my exhibition. It is of a sculpture titled Phantom Limb, and it sits in the vestibule of First Presbyterian Church in Ann Arbor. Its absence in the gallery space is important as it forms a cross-disciplinary conversation that is so important to my work. The half-burned away pew floats ominously above a wooden plinth supported only by a bronze leg, referencing both the form and materiality of a monument, but the work was made in mourning, once again thinking about the belief systems that prop society up, and the public memories we choose to evoke. In the vestibule, this piece finds itself home among the plaques and furniture of the church sitting room; a work to discover, ever-present but not necessarily jumping out at you, and so different than a piece sitting stark and powerful against the non-neutral walls of the gallery space.